Introduction

In initial exchanges with our clients, the question of annotation accuracy is systematically at the center of discussions. Whether it concerns bounding boxes or segmentation masks, the requirement is often the same: obtaining annotations that are as precise as possible, with pixel-level alignment.

This request is legitimate, as intuition dictates that the more precise the annotation, the better the model’s final performance.

However, this pursuit of geometric perfection raises a critical question for engineers and project managers: does this additional human investment truly translate into an equivalent gain in your model’s algorithmic metrics (mAP, IoU)?

We will analyze, based on the results of several recent studies, how different types of annotation imperfections actually affect model performance, and where the balance point lies between annotation effort, cost, and algorithmic gain.

Definition of Key Metrics

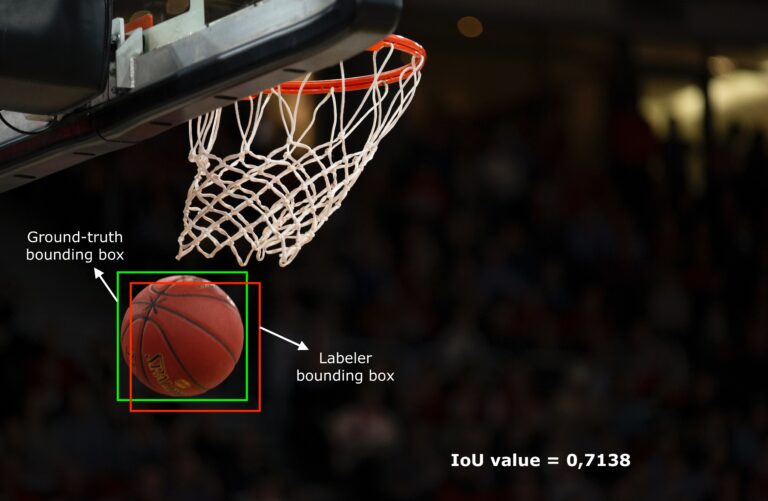

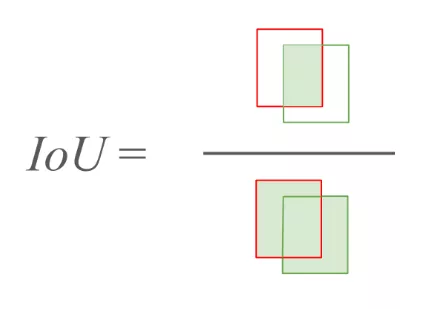

IoU (Intersection over Union): This metric measures the accuracy of object localization. It calculates the overlap between the model’s prediction and the ground truth.

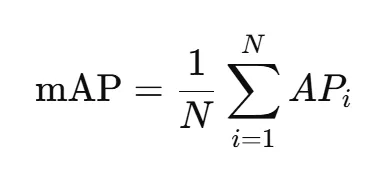

mAP (Mean Average Precision): This metric measures the overall quality of an object detection model.

It combines both precision (how many detections are correct) and recall (how many objects were detected out of all present). First, the average precision for each object class (AP) is calculated, then averaged across all classes to obtain the mAP.

1. The Diminishing Returns Phenomenon: Bbox and Geometric Noise

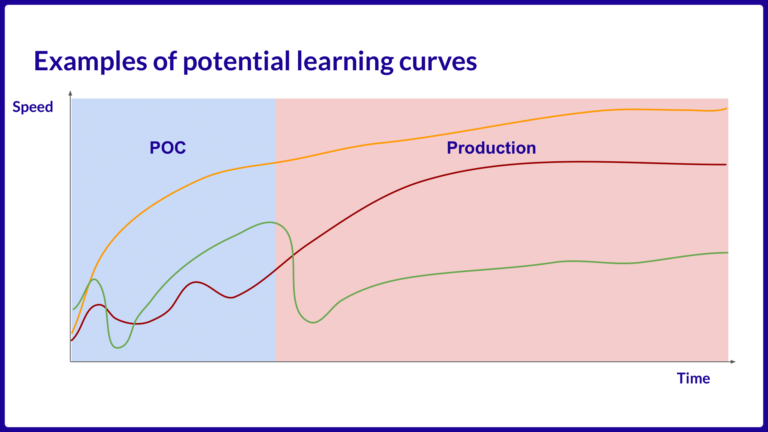

Human investment in geometric accuracy follows the rule: cost increases exponentially as one approaches perfection (correcting minor errors, multiple review cycles). Yet, model performance does not follow this curve.

Universal Noise Annotation Study

The Universal Noise Annotation study sought to quantify the real impact of annotation imperfections in bounding boxes (Bbox). The researchers implemented a rigorous methodology:

- Datasets and Models Tested: The analysis was conducted on benchmark datasets (e.g., COCO), testing the robustness of several state-of-the-art object detection architectures (often including R-CNN or Transformer-based models).

- Systematic Noise Injection: Rather than using “naturally” noisy human annotations, the study simulated and injected annotation errors in a controlled manner, varying the rate and type of noise (5%, 10%, 20% of annotations corrupted) and measuring the corresponding mAP drop.

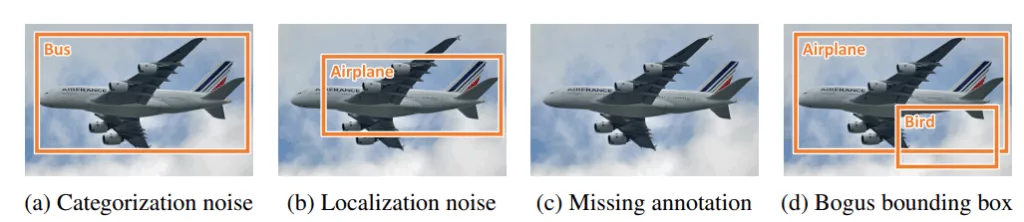

Three Major Noise Categories

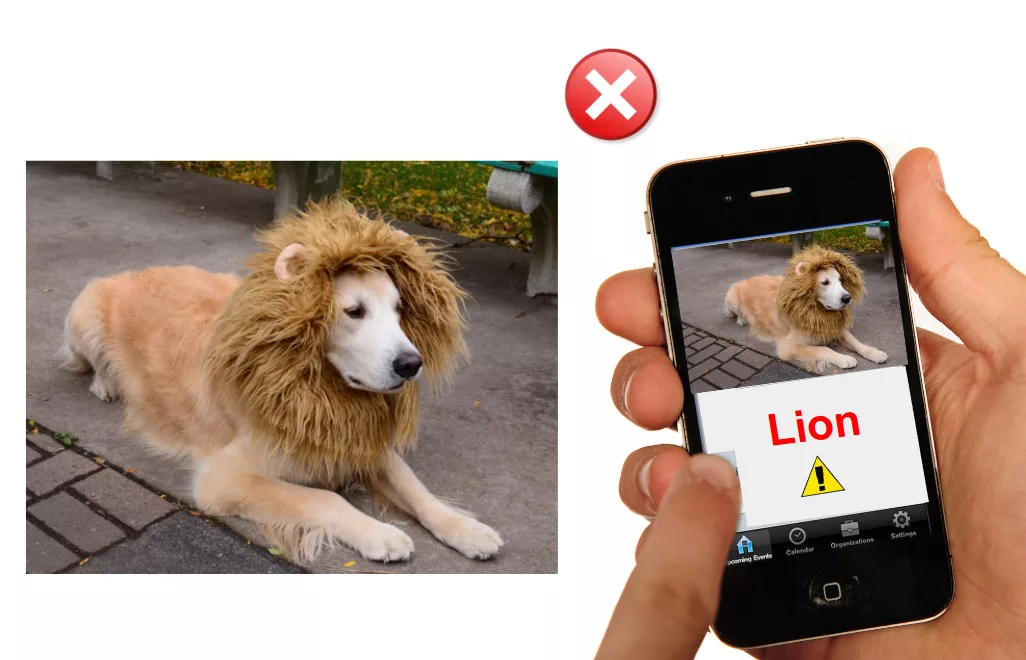

- Classification Noise (Categorization): Assigning an incorrect class label (e.g., labeling a “car” as a “truck”).

- Geometric Noise (Localization): Shifts, resizing, or imperfect bounding box contours.

- Presence Noise (Missing or Bogus): Forgetting to annotate a visible object (false negative) or annotating a nonexistent object (false positive).

Key Result: Tolerance to Geometry

The finding is clear: the tested models are tolerant to moderate geometric noise.

Even with a significant amount of simulated localization errors, algorithms showed minimal mAP performance drop because they continue learning contextual features and the visual signature of objects.

Investment to eliminate the last margins of geometric error follows the law of diminishing returns. The extra effort required to move from an average IoU of 0.85 to 0.90 is disproportionate compared to the final detection gain.

Moreover, the study showed that models are much more sensitive to Classification Noise and especially Presence Noise. Forgetting to annotate an object (or giving it the wrong label) has a far more destructive effect on mAP than slightly misaligning its contour.

When all three types of noise (classification, geometry, presence) are combined beyond a certain threshold, performance collapses sharply.

Implication: Annotation effort should focus on semantic accuracy and completeness (missing nothing), not on geometric perfection.

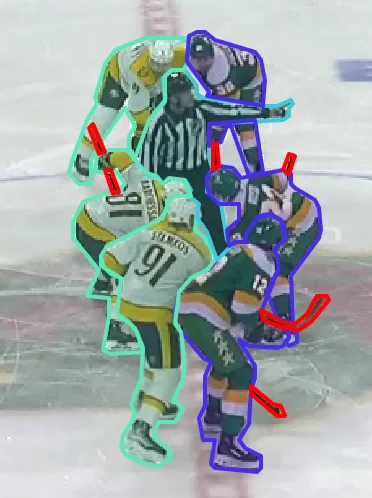

Example: For bounding boxes of ice hockey players for our client, moving from a “perfect” Bbox to a more approximate Bbox can double or triple annotation time:

2. Bbox vs Segmentation: Justifying the Geometric Cost

If moderate Bbox inaccuracy is tolerated by the model, what about instance segmentation? Segmentation offers higher precision but comes with intrinsically higher annotation cost. The question becomes: is this precision justified by the task, or is it an unnecessary expense?

Cost-Time Gap

The cost difference between Bbox and polygon segmentation is significant:

- Annotation Cost: Based on our experience, depending on image quality and object complexity, annotating a Bbox can take 3–10 seconds, whereas a mask can take 20 seconds to several minutes.

- Consequence: Paying significantly more for segmentation must be justified by technical imperatives where precise contours, shapes, or area measurements are critical (e.g., medical imaging, path or trajectory calculations for autonomous systems, or defect inspection).

For tasks focused on localization and counting (where IoU of 0.7 is sufficient), investing in segmentation is a resource optimization mistake. It is better to use those resources to increase dataset quantity and diversity, a much more powerful performance lever.

Practical Case

For our client, we enriched bounding box annotations for player detection with segmentation masks. This approach enables better instance separation in high-density scenes, especially during player clusters or partial overlaps, where bounding boxes alone reach their precision limits.

Additional example: Using masks to detect different zones of the playing surface for precise localization:

Note: Recent research shows that models specifically designed to handle noise, such as those based on Vision Transformers and Adaptive Learning (ADL) strategies, can actively compensate for noisy annotations, achieving reliable results even when training data is imperfect (see: Dealing with Unreliable Annotations: A Noise-Robust Network for Semantic Segmentation through A Transformer-Improved Encoder and Convolution Decoder).

3. Technological Intervention: SAM and the End of Costly Human Annotation

The advent of foundation models in computer vision, such as Meta AI’s Segment Anything Model (SAM), transforms segmentation annotation. Trained on the massive SA-1B dataset (over 1 billion masks), SAM can generalize and produce precise segmentations, including for previously unseen objects (zero-shot learning).

Increased Efficiency and Precision

Integrating SAM into annotation tools allows generating high-quality masks from a single Bbox or point. This significantly speeds up annotation, reduces human errors and inconsistencies, and lowers overall cost while improving productivity.

For high-precision projects, model-in-the-loop annotation becomes the most effective method: human effort focuses on validation and quick refinement of AI-generated masks, rather than exhaustive manual creation.

The introduction of SAM therefore reshuffles the deck by significantly reducing the cost of accessing high-quality annotations. By automating or effectively assisting fine segmentation tasks, SAM allows for increased investment in annotation quality without proportionally increasing costs or timelines. This makes high-value datasets more accessible, previously reserved for projects with large budgets.

Example: Hockey player annotation using SAM with bounding box selection followed by minor corrections by the annotator.

Note: For smaller or blurrier objects, SAM is not always the fastest solution.

⚠️ Data Privacy: Using external models like SAM may be limited for sensitive data (e.g: personal, medical, or industrial secrets). Such tools often require data transfer to the provider’s annotation platform. In these cases, regulatory constraints (GDPR, data ownership) may necessitate manual annotation, even at higher cost.

For a deeper dive into the strategic advantages of this technology, explore our comprehensive guide on SAM in Data Annotation: When and How to Use It?

4. Data Strategy: Calibrating Annotation for Optimal Impact

The best approach is to adapt annotation effort to the real task needs, leveraging model robustness and advanced tools like SAM for segmentation.

- Define the functional threshold: Set the minimum IoU or segmentation precision required for your application. If IoU of 0.7 or a slightly approximate mask is sufficient, seeking geometric perfection (IoU > 0.85) represents diminishing returns.

- Optimize quantity and diversity: Resources saved by foregoing over-precision can be reinvested in increasing the number and variety of annotated data. For most models, more diverse data with “very good” accuracy outperforms a small amount of perfectly annotated data.

- Leverage model-assisted annotation: Tools like SAM can quickly generate high-quality masks from simple points or bounding boxes. Human effort shifts from full annotation to validation and refinement, reducing time and cost while maintaining high consistency.

Conclusion: Annotation expertise is no longer about geometric perfection, but about designing an intelligent data strategy: calibrate precision, maximize diversity, and leverage AI tools for optimal algorithmic gain at controlled cost.

Let’s discuss your data strategy to identify your optimal balance point.

Do you want to align the precision of your annotations with the actual needs of your AI models?